By Valeria Hänsel and Kerem Schamberger

In the early hours of 14 June 2023, a fishing boat sank off the Greek coast near Pylos. The some 750 people crammed on board had almost made it all the way from Libya across the Mediterranean to Europe. But most of them would not survive the encounter with the Greek coast guard. According to the few survivors, the coast guard tried to pull the boat from Greek to Italian waters by rope in an effort to dodge responsibility. Instead of rescuing them, they caused the boat to capsize. It sank in the space of just minutes, taking the people with it.

Making victims culprits

Afterwards, nine of the survivors were arrested. The charge: people smuggling. They are in custody awaiting trial and the possibility of a life sentence. This is how they are making refugees themselves take the blame. The real culprits get off scot-free - those who are forcing people onto ever more precarious routes and putting their lives in danger with their closed-border policies.

Pylos is not an isolated case: in Greece alone, more than 2000 people are behind bars brandished smugglers, the second largest prison population in Greece overall. Thousands also languish in prison in Italy and Spain for the same “criminal offence”. Their only crime: crossing a border in search of a better life and helping others to do so. Whilst for anyone with a German passport border crossings are a matter of course, for others the penalties are harsher than for murder.

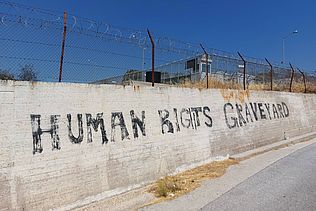

Greek prisons are usually overcrowded, there is insufficient medical care, and violence occurs repeatedly. Last year, the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment stated that the prison conditions were “an affront to the human dignity of the prisoners”. For years or even decades, people have been shut off from the outside world under these conditions.

“People smuggling” is subject to heavy criminal penalties throughout the EU: At Europe’s southern border in Italy and Spain, at the Polish-Belarusian border and along the Balkan route, people helping refugees are arrested time and again. The criminalisation of people facilitating migration even extends all the way to the Sahel region, for instance to Niger. The EU has forced legislation on the country which overnight has turned drivers on the migration routes into “criminal smugglers”.

The criminalisation paradox

Making border crossings illegal is paradoxical: refugees have the right to have their claim to asylum reviewed individually. To claim this right, though, they are first forced to get to the place where they can apply for asylum. This requires them to cross borders. But because the policy of sealing off borders makes it illegal to cross them, refugees are structurally forced to break the law. In this situation, there are people who help them cross the border: People who are then called aiders and abettors, smugglers or traffickers. If this policy of sealing off borders were not in place, there would be no need for them. Only when borders are demarcated and crossing them is criminalised do smugglers become a necessity and can they set their own terms. No one would spend hundreds of dollars to get into an unseaworthy dinghy if they could book a ferry ticket for far less money. As long as European borders are militarised and closed, there will be people helping refugees, smugglers and traffickers.

Violent and exploitative economies can form in the shadows of the border walls. Criminals and cartels who exploit the hardship to make money. But this problem is created by the border regime itself. It takes on even more bizarre dimensions: For instance, the EU finances the so-called Libyan Coast Guard, which intercepts people fleeing to Europe, takes them to prisons, tortures them, sells them on slave markets, and at the same time itself sells refugees options for crossings to Europe. A business in line with the EU border regime, at the expense of human beings.

Smugglers as heroes

The division of the world into nation states, nationalities and passports is a recent phenomenon historically speaking, as is making border crossings illegal. A look back in history shows us that the social image of people smugglers depends on the historical situation in question. In Germany, the memory of people smugglers who made it possible to flee from East to West Germany when Germany was divided has downright positive connotations. Various spectacular escape stories, such as tunnelling under the Berlin Wall, have been turned into films or TV programmes. Smugglers who saved the lives of thousands of those persecuted under National Socialism are also venerated today. One of them is the anti-fascist Lisa Fittko, who was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for leading dozens of people persecuted by the Nazi regime from occupied France over the Pyrenees to Spain in the 1940s, including Walter Benjamin. There are also examples of smugglers from many other eras and continents who are now considered heroes. In the US context, Harriet Tubman is the best-known, who after her own escape as part of the Underground Railroad in the 1850s, brought enslaved people from the South to the Northern states.

We can assume that even those who are being criminalised as so-called smugglers in the EU today will one day be viewed differently. Once the political contexts they come from are better understood, their stories are told and their courage in saving others is recognised - even if their skin is not white and it takes political education and empathy to understand their lives. Time will bring this recognition. But solidarity and support are what those helping refugees need now as they are being criminalised and put behind bars. The case of the accused survivors of the boat that sank off Pylos once again brings into sharp relief just how urgently this is needed.

This text is based on a speech given by Valeria Hänsel and Kerem Schamberger at the “Berlin Day of Smuggling - Festive Tribute to Europe’s Smugglers and Traffickers” on 25 June 2023. Click here to watch.