The city of Cox’s Bazar is deep in south-east Bangladesh, the holiday resort of the country’s middle class. Directly on the world’s longest sandy shore, skyscrapers tower side by side, each offering guests an unobstructed sea view and all the other holiday pleasures. For us, it’s the start of a journey which takes us to a totally different planet less than an hour to the east by car. We’ve hardly left the last suburb of Cox’s Bazar when a hilly landscape opens up, with rice growing in its green valleys. The hills, however, have lost all their greenery. They are terraced and occupied by thousands upon thousands of huts, mostly of the simplest construction, a thin frame of bamboo covered in plastic sheeting.

Paths wind between the huts, leading from one hill to another, carrying an endless stream in both directions of pedestrians, men, women, children, with wildly honking auto rickshaws, jeeps and minibuses careening through them, also in both directions. We’ve reached the Rohingyas, Muslims expelled from neighbouring Myanmar. The first of them arrived in the 1970s after the first major ethnic cleansing, with more following in 1992 and 2012, around 300,000 people in all. Since August 2017 the number has grown to over a million.

The new arrivals are the survivors of the latest wave of ethnic cleansing – an attempted genocide by the Myanmar army, supported by the Buddhist majority in Myanmar’s population, and covered by Nobel Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, de facto head of government.

Kutupalong, Balukhali, Bag Ghona

With colleagues from the Bangladeshi medico partner Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK, people’s health centre) as our guides we spent two days at the Kutupalong, Balukhali and Bag Ghona camps. The noise, the smells, the throng of humanity are indescribable. All three camps are completely overcrowded, with new arrivals cramming more huts into the remaining free spaces. The situation is worst at the Kutupalong camp, where huts often support each other, and anyone leaving their home steps directly into the traffic chaos. Between the huts are the simplest imaginable booths offering everything and nothing – biscuits, vegetables, dried fish, cigarettes, unchilled beverages. They are run by Bangladeshi and also Rohingya who managed to take some money or jewellery with them. Their buyers have previously bartered rice, lentils or clothing distributed by the aid organisations, without which there would be no survival here. Peddling, preparing and eating meals and the daily patching of the bamboo huts are the only things for people to do.

The rest of the day is spent waiting – waiting for an argument in the neighbourhood, for the arrival of a lorry with rice or clothing, for new arrivals who need to find a place. And otherwise, waiting for nothing. We feel the tension in the air when we reach a square where rice is just being distributed. Because the space is too small, the queue of people waiting goes all the way around the square. At the lorry where the sacks of rice are being handed out, there is a hectic scrum, with men in uniforms and Rohingya auxiliary police in civilian clothes using long staves to push back the screaming people who are rushing wildly back and forth and grabbing for the sacks. A sack bursts, and the white grains fall on the sandy soil.

People’s health centres

GK has a total of 13 health stations in the three camps, where doctors, trained paramedics and volunteers work, including young Rohingya. They offer a simple basic health service in tents or large huts, divided up by plastic sheeting. There’s a waiting area, a room for admissions, the room where the doctor sits, a room for psychosocial emergency aid and a room for dispensing medications. A psychologist tells us what she’s been told, stories of death, violence, utter contempt, of the strain of flight, the lack of prospects. There is also the fate of an old man who collapses by the roadside somewhere and can’t even manage to take the spoon of broth that someone offers him.

At some of the health centres, children are being given food supplements. If someone is seriously ill, GK staff take them to one of the larger field hospitals – but they’re also limited in what they can do. It’s easy to die on the planet of the Rohingya.

Another health centre is exclusively for treating diarrhoea patients. We arrive in the middle of an urgently called meeting. Diphtheria has been spreading for two or three days, and the number of those infected is doubling daily. The colleagues here are extremely worried, and decide to reserve this station for diphtheria sufferers. “There’s too little vaccine,” the director tells us, “and even if we get more, that will only help to a limited extent, because the vaccine needs a couple of days to take effect. We’re also lacking drugs to treat the disease.”, she adds.

Genocide

As we move on, the call of a muezzin sounds from a tent in the middle of the sea of huts, broadcast over two megaphones fastened to the top of a long pole. We talk to a group of young men, Rohingya, who are working as Community Health Workers under the direction of GK. We ask them about their expulsion from Myanmar. They all tell the same story, of soldiers storming their village, firing into houses, shops, schools and mosques, driving people onto the streets and putting them to flight, giving them just time to take a few belongings. Individual men and women were seized at random, some shot directly, others dragged off, raped, tortured. While the survivors fled in panic, their houses were set on fire behind them, gardens and fields devastated, livestock killed.

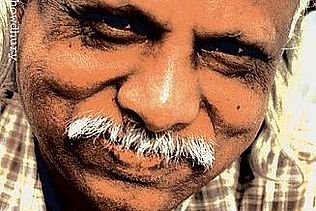

One of the young Rohingya keeps to the side and stays silent. I ask if I can photograph him, he agrees. His name is Shafik, he’s from the village of Talatule in Rakhine, which is the name of the Rohingya settlement area in Myanmar. He and his brothers are the only survivors of a family of twelve.

Lost cause

On the evening of the first day we meet a Rohingya activist at a restaurant in Cox’s Bazar. He’s in his late twenties, studied for a couple of years in Bangladesh, and returned to Myanmar in 2012, after the partial withdrawal of the military from power. As a member of an activist network which documents the situation of the Rohingya and publicises it worldwide, he – like many others – voted for the party of the military, which had promised to include Aung San Suu Kyi in the government. “Our hopes were betrayed. The so-called democratisation only applied to the Buddhists, we were worse off than before. The new government declared unmistakably that it would not restore our citizenship. Revoking this in 1974 made us nonpersons in our own country.”

Because the military had their sights on him, he fled to Bangladesh in 2016, a year before the latest wave of expulsions, lives there with a false passport and continues his political work. In our discussion we go through all the possibilities open to the Rohingya. They won’t all be able to stay in Cox’s Bazar: currently there are twice as many Rohingya there as the original Bangladeshi inhabitants, and tensions are rising daily, despite the initial solidarity and aid. The Bangladeshi Government has tried to reach a resettlement agreement with Myanmar which would guarantee the Rohingya the restoration of their citizenship, reconstruction of their homes and return of their property.

Myanmar was unwilling to make any concrete commitment. Even so, Bangladesh signed the agreement, under massive pressure from India, Russia and particularly China. Rakhine, home province of the Rohingya, is rich in mineral resources, and Russian, India and China want to secure their exploitation. Within the framework of the Chinese “Shanghai-Calcutta Corridor” Rakhine is scheduled to be a giant free trade zone. Because they would be opposed to the destructive conversion of their country into an “export processing area”, the traditional inhabitants have to go – a process which is used elsewhere in the world as well. The labour needed for the future mines and factories will then be brought into the country as “fresh blood”. As foreigners, their only concern is their income, progress and development.

The right to stay, the right to go

“Bad though the economic scheming in Myanmar is, the racism is worse,” the activist tells us, “they hate us. This is why the Mynamarese also believe the ridiculous lie that we’re illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. If we return to Myanmar, they’ll treat us like those who returned from earlier expulsions, they’ll shut us up in camps, and that’ll be the end of us.”

Like our contacts in Kutupalong, Balukhali and Bag Ghona, the activist believes that the Rohingya will refuse to return to Myanmar. As it’s relatively unlikely that the Bangladeshi Government will drive them back by force, the planet of the Rohingya will remain for two or three more years. We agree that international pressure is needed on both governments. However, support from Malaysia and Indonesia won’t be sufficient. “We can only rely on the EU and the USA.”

We look at each other in embarrassment: we see no hope of this. Although Bangladesh is the most densely populated plain in the world and is a poor country for most of its inhabitants, several Bangladeshis have told us they would be prepared to accept the Rohingya permanently, naturally not just in the Cox’s Bazar district, but spread over the whole country.

Several intellectuals have already called publicly for giving them citizenship immediately. The Awami League governing party is advertising aggressively for votes for their Prime Minister Sheijk Hasina with the slogan “We can do it!”, and hundreds of posters and banners calling her the “Mother of Humanity”, “Champion of Global Peace” and “Last Hope of the Oppressed”.

GK colleagues estimate that around half the people of Bangladesh would accept such a solution. Many Rohingya have already made their choice. As the camps are open, every day people set out inland on their own, knowing that the garment factories in the megacities of Dhaka and Chittagong are looking for new labour every day. “Perhaps we could survive like this,” the activist says, “but only as individuals. As the Rohingya people, we would disappear.” We end our discussion with the bitter insight that for now we have to rely on the continuation of the status quo, on the planet of the Rohingya in the hills above Cox’s Bazar. As long as it is there, at least the camp will remain open for the Rohingya.

Our colleagues with GK will also be staying. They explicitly support the public declaration of several international aid organisations that they will only work in returnee camps in Myanmar if there’s a guarantee that the demands of the Rohingya will be met, namely recognition of citizenship, settlement in their home areas, reconstruction of the destroyed villages and municipalities, investigation of the crimes against the Rohingya.

medico supports the Emergency Aid of our partner GK and asks for your backing: Stichwort: Bangladesch